This is

first of a series or articles which will examine nibs and

their shapes in detail. Bruce gives an introduction to the

Scanning Electron Microscope and shows some preliminary images

to give you an idea of what this equipement is capable of.

A Q&A will be run in conjunction with this article, to

participate please click on the link in the related links

box on the left..

Scanning

electron microscopes have been available since the mid 1960s.They

can achieve much higher magnification and have a better depth

of field than optical microscopes. This is an big advantage

for examining large curved things like nibs.

SEMs work

by firing a finely focused beam of electrons, in a vacuum,

at the sample. The beam is rastered sequentially across the

surface of part of the sample. Some of the electrons are reflected

back from the specimen, detected and displayed to form the

enlarged image direct on a computer screen, and captured digitally.

Sadly, electron microscopes only work with monochromatic electrons

(of one energy), so the pictures are inherently black and

white. There are techniques for later colouring the images.

As well,

the beam of electrons can be used to analyse non-destructively

individual points on the sample, for instance, to identify

the elements present in the "iridium" on the point,

and the differences in composition where the "iridium"

is welded to the gold of the nib. This is because the impinging

electrons interact with the elements present where the beam

hits. The gold atoms emit characteristic gold X-rays and the

silver and copper atoms emit silver and copper characteristic

X-rays, and these are proportional to the amounts of each

element present. The X-rays are collected by an X-ray detector

attached to the SEM.

A relatively

hard part of imaging the nibs is getting an evenly illuminated

image, without some sections being too bright and some parts

being in the darker shadows.

Chosing

the correct angle to show the aspects desired is also a challenge.

Logically,

an SEM in Australia can now be operated directly over the

Internet, or the images viewed remotely in real-time from

the US or anywhere. However, SEMs are common in Universities

and research laboratories, so there should be some in most

major cities.

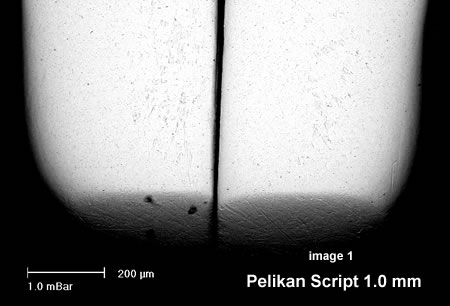

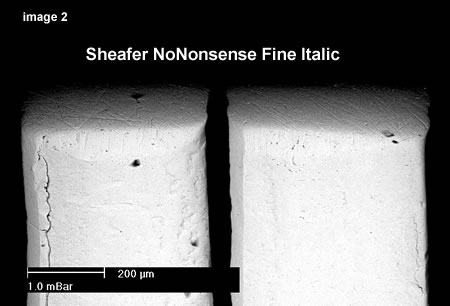

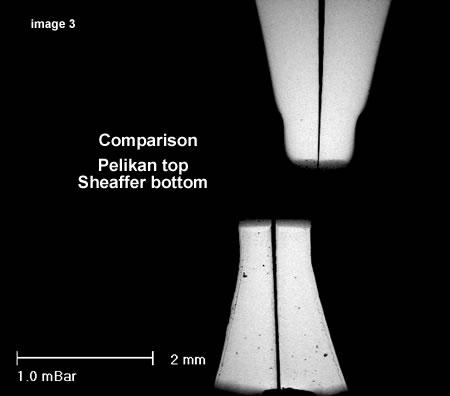

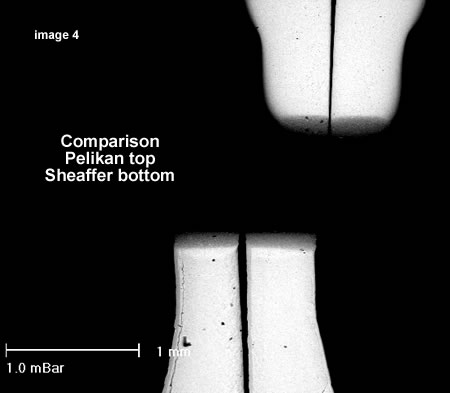

The illustrations

show some preliminary images from a recent Pelikan Script

1.0 mm low-price pen (sort of calligraphy) in image1, and

a standard Sheafer NoNonsense Fine Italic (which I bought

second-hand on Sunday for Aus$2. The Sheaffer is much squarer

("Italic") image2, and the Pelikan much rounder

and "Stub". The nibs are mounted upside-down, and

we are looking straight down at the underneath of the nibs.

One advantage

of the SEM is that one can measure the dimensions relatively

accurately from the scale on the images(at least laterally

in the image if not vertically), and there is a good idea

of the shape, and the smoothness.I suspect that the very fine

scratches and features are not as important in nib-smoothness

as the actual shape and other factors. Obviously experts like

John Mottishaw who work with a good optical microscope will

have a very good feel for the parameters that matter.

|